Fahrbach: 12-String harp guitar

Fahrbach: 12-String harp guitar |

Some 19th century guitars had more than 6 strings in order to extend the instrument's range. Usually, these extra strings were bass strings tuned in pitch below the guitar's low E string. This was not a surprising development, since the first 6-string guitar was simply a Baroque 5-string guitar fitted with an extra 6th bass string. There was tremendous experimentation with guitar design in the 19th century as evidenced by the wide array of body shapes, designs, and decorations, as well as the number of strings. There is some evidence to suggest that perhaps single-course 7-10 string guitars and guitar-lyres may have been invented before the 6-course guitar which was first double-strung. The extra strings were attached either to the side of the headstock, or by using a double neck. The construction must be slightly altered to widen the bridge, and also to handle the extra tension of additional strings. Unfortunately, if the bridge is too tight by over-compensation, the tone quality of the guitar will suffer, or sound different from a 6-string. A high quality multi-bass guitar with a great 6-string sound requires a skilled luthier to balance the tension requirements with tone production. Whether or not guitars existed in this time period with fretted 7th-10th courses is a subject of some debate. According to Matanya Ophee, in his article on the Lyre Guitar in the "New Grove" based on an earlier article: "M. Ophee: -The Story of the Lyre-Guitar-, Soundboard, xiv (1987v8), 235v43": "The article includes photos of lyre guitars with 9 strings, all under the fingerboard. (These were instruments in the collection of Robert Spencer, now at the RCM in London)." Ophee goes on to say, "There is no question that the 7-string on the fretboard design existed already in the last decades of the 18th century. It may be true that Stauffer and Panormo did not make guitars with 8 fretted strings, but such guitars did in fact exist. Several sources, including the Doisy method of 1801, speak of guitars and lyre guitars with up to 9 courses on the fingerboard, some single strung, some double and some even triple." In addition, the Russian 7-string guitar in the 1820's and possibly earlier was fretted across all 7 strings, as is evident by examining the scores. |

The "Harpolyre" was patented by Jean Francois Salomon in 1829. Gregg Miner explains this instrument on the following web page: Harpolyre Page.

According to Richard Long in GFA Soundboard Magazine, Vol. XXXIV, No. 3, 2008 on page 86-87, "The new instrument had 21 strings on three necks; the central neck (manche ordinaire) was tuned like a standard guitar... Above the central neck was the chromatic neck, with seven silk strings with metal windings. Below the central neck was the diatonic neck, with eight gut strings.... the designations or, di or ch above certain notes [refer] to the neck on which the notes are played."

According to Matanya Ophee, "This was an instrument with three necks with a total of 21 strings. It was invented by one fellow named Salomon, who also wrote a method for it. Several people wrote music for it, including Sor, Carcassi and de Fossa. But like all white elephants, it never survived. There is one of these in the Metropolitan Museum in New York."

The Sor harpolyre pieces are published by a Japanese publisher, Gendai. See Sor-Gendai. They are in Vol. 9 GG309. Simon Wynberg has recorded the Marche Funebre on the Chandos label (thanks to Dave Starbuck for pointing this out).

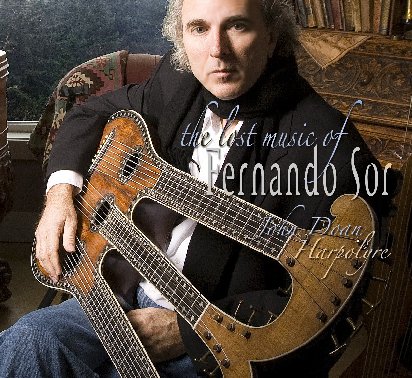

There is a CD by John Doan, titled "The Lost Music of Fernando Sor" recorded on an original 1830 Harpolyre instrument. There are also videos of Doan playing the Harpolyre on YouTube; superbly played and using what I consider authentic period technique as well. The sheet music has been published in 2017; arranged for 6-string guitar, with low basses notated (8vb) for guitars with more than 6 strings (in order to render all of the original notes in their octaves as written). These are characteristic pieces of Sor, very fine compositions.

The "Harpolyre" was patented by Jean Francois Salomon in 1829. Gregg Miner explains this instrument on the following web page: Harpolyre Page.

According to Richard Long in GFA Soundboard Magazine, Vol. XXXIV, No. 3, 2008 on page 86-87, "The new instrument had 21 strings on three necks; the central neck (manche ordinaire) was tuned like a standard guitar... Above the central neck was the chromatic neck, with seven silk strings with metal windings. Below the central neck was the diatonic neck, with eight gut strings.... the designations or, di or ch above certain notes [refer] to the neck on which the notes are played."

According to Matanya Ophee, "This was an instrument with three necks with a total of 21 strings. It was invented by one fellow named Salomon, who also wrote a method for it. Several people wrote music for it, including Sor, Carcassi and de Fossa. But like all white elephants, it never survived. There is one of these in the Metropolitan Museum in New York."

The Sor harpolyre pieces are published by a Japanese publisher, Gendai. See Sor-Gendai. They are in Vol. 9 GG309. Simon Wynberg has recorded the Marche Funebre on the Chandos label (thanks to Dave Starbuck for pointing this out).

There is a CD by John Doan, titled "The Lost Music of Fernando Sor" recorded on an original 1830 Harpolyre instrument. There are also videos of Doan playing the Harpolyre on YouTube; superbly played and using what I consider authentic period technique as well. The sheet music has been published in 2017; arranged for 6-string guitar, with low basses notated (8vb) for guitars with more than 6 strings (in order to render all of the original notes in their octaves as written). These are characteristic pieces of Sor, very fine compositions.

|

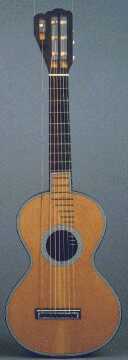

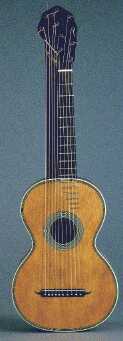

The Lacote Heptacorde Model was derived from collaboration with Napoleon Coste. A few surviving instruments exist dating from the late 1830's into the mid-1850's. This instrument design won Lacote an exposition medal in 1839, which was mentioned in several Lacote labels after 1839.

The 7-string guitar had an extra "floating" bass string above the fretboard. It was only utilized for the open drop D, and occasionally tuned to C.

Much of Napoleon Coste's music was written for 7-string guitar (as was music by his associate Søffren Degen (1816-1885) ). Their music can be played on a normal 6-string guitar, but the low bass notes must be transposed up an octave. The extra low bass also allows many drop-D pieces to be played without de-tuning, or to occasionally drop the octave of normal D's for added resonance or emphasis especially at cadence points.

The Lacote Heptacorde on the left is in the private collection of Bernhard Kresse.

This model of Lacote is called a Heptacorde (e.g. Seven String Guitar). It was apparently derived from collaborations between Rene Lacote and the famous French composer and student of Fernando Sor, Napoleon Coste, who composed for and advocated the 7-string guitar. Later Heptacorde models introduced the tail piece and extended fretboards, while earlier examples had flush fingerboards and a pin bridge. There are very few surviving original Lacote Heptacorde guitars. This model of guitar is shown in two famous photos of Napoleon Coste. Two excellent articles can be found on the Harp Guitars site:

Harp Guitars Lacote Heptacorde article Harp Guitars Lacote Heptacorde and Decacorde article Two surviving photos of Napoleon Coste exist with this guitar model (see the Composers page of this site), which was apparently his primary instrument for composing and concertizing. Note that the photo of an older Coste shows the guitar design had evolved to include the tail piece and pass-through bridge, while the younger Coste photo shows the pin bridge. Both photos show the 7-string distinct machined headstock with enclosed Lacote patent tuners. |

|

The pictures at left are of a French guitar from Mirecourt restored by Bernhard Kresse and owned by Raphaella Smits, and played on her CD. Original period 7-string guitars are rare. According to Kresse, the extant early 19th century extra-string guitars have wider necks. The first 6 strings are fretted and the additional strings are beside the fingerboard (floating). On Lacote's 10-string guitar with a wider neck, the frets stop after the sixth string. |

|

The 1820 7-string shown left is from the Musee de la Musique - another example of the Coste-style 7-string guitar with the normal 6 strings plus an added drop D in the bass. Most likely, this guitar was not built in 1820, but may have a Lacote label of "182_" which was used well into the 1830's.

|

|

The 8-string guitar is a good compromise between the 7 and 10 string guitar. It provides the same range as the 10-string, although scordatura and fretting of bass notes is sometimes required. To improve playability, my duet partner, an amateur luthier, had the idea of making slight adaptations to early 19th-century designs, so that a fully-fretted 8-string neck can be adapted to the 19th century guitar body. Kenny Hill built a fine 8-string Panormo-based design to my duet partner's specifications (first picture to the left). Based on observations of the Hill guitar and several other multi-bass guitars, as well as extensive correspondence with luthier Bernhard Kresse, Mr. Kresse built my personal guitar to my specifications based on an adaptation of the Anton Stauffer design to the 8-string, a fantastic concert guitar in every aspect (second picture to the left). This is a modernization of the 19th century design as Staufer did not build frettable 8-strings. The 8-string is usually tuned 7=D 8=A. However, some pieces require one string tuned to C; for example, Legnani's 8-string pieces call for an open low C.

Advantages:

|

|

This period floating 8-string guitar made by Reis in approximately 1840 is a rare surviving example of the multi-bass guitars. It is patterned after the famous Viennese builder Anton Stauffer, as many Viennese builders copied Stauffer's design. This guitar has a robust tone and is recorded on the CD Romantic Guitar - Brigitte Zaczek. Note that the extra 2 strings are not fretted and only the open string can be played. The headstock is a typical figure 8 shape, where the assembly for the 7th and 8th strings is interlocked with the figure 8. Although the extra bass notes provide the Drop-D and Drop-A, the lower bass notes vary in distance from the sixth string. This design can cause playing accuracy problems when playing tasto or ponticello. The bass notes can be tuned to A, B, C or any note which suits the music. |

|

The Carulli DecacordeOne form of 10-string guitar was called the Decacorde. Rene Lacote made several 10-string guitars, which were likely played by Carulli and others. Shown are a Lacote 1826 and 1830 from Musee de la Musique. The Carulli-style Decacorde has 5 fretted strings and 5 floating basses. I have strung and tuned my 10-string guitar according to Carulli's Decacorde method facsimile in order to try it out and provide a first-hand report to the readers of this site. A modern 10-string guitar works fine, but be sure to use appropriate string gauges and tensions (I used a set of normal classical guitar strings for strings 1-5, use a high tension 5th string for 6=G because it is tuned a step below A, for 7=F use a low tension 6th string because it is tuned up a half-step, use a normal 6th string for 8=E, use a high tension 6th string for 9=D which is drop D tuning, and use about 2 gauges higher for the 10th string C.) The Carulli Decacorde method, opus 293, describes the tuning as: C', D', E, F, G, A, d, g, b, e'. Strings 1-5 are tuned the same as the standard guitar. In Carulli's time, the guitar very recently changed from a 5-course instrument to a 6-course instrument, and so having the top 5 strings the same must have seemed very natural to many guitarists of the day. The remaining bass strings are tuned in descending order step-wise, e.g. 6=G, 7=F, 8=E, 9=D, 10=C. Scordatura is intended for the basses as needed by key. The basses can be tuned by a half step according to the key signature, e.g. the 7th string may be tuned to F#, 10th to B, etc.. Carulli explains the tuning in the method and has various exercises for different tunings and key signatures. Unfortunately, aside from the music contained within Carulli's method book, I have not located any further music specifically composed for Carulli's Decacorde. However, the tuning is perfectly adaptable to playing any standard guitar repertoire, and it is especially effective at handling transcriptions where bass notes (especially F and G) are problematic to sustain or to reach when a counterpoint treble melody is in a high position. In Baroque lute transcriptions the open strings for C, D, E, F, G, A allow bass notes to be sustained as written, and facilitate the fast-moving "walking" bass lines found in Weiss, Baron and others. With the open basses, and tuning the basses according to the key signature (for example tuning 5=A-flat and 6=E-flat for the key of C-minor with 3 flats), it is usually possible to play every note with no alteration to the transcription, and with no awkwardness in hand position. There are two negatives however with this tuning: 1. It is awkward to learn at first, especially to accurately hit the E bass string on the 8th string. 2. Compared to so-called "Romantic Guitar" or "Baroque" tuning of a 10-string (10=A octave below 5th string, 9=B, 8=C, 7=D), the Carulli Decacorde has no basses lower than C, which means raising the octaves of basses if the original source uses the extended range. In a suite by Baron for example, only 2 notes in the entire suite were lower than C (both B-natural), thus it seemed a good compromise. With some Weiss pieces that use low basses extensively, the transcriber may be better off in using the A/B/C/D tuning. |

|

This instrument is an 18th century 10-string guitar, with 10 single string courses. It pre-dates the Carulli-era 10-string guitar and must have co-existed with the very earliest 6-course guitars invented.

"An arch-guitar by F. FIEVEZ in LILLE. XVIII° c. Label printed: "F. FIEVEZ. Md. LUTHIER / PLACE DE RIHOUR A LILLE". Maple back and ribs, edged with blackwood. Spruce table and soundhole edged with composed ebony - maple. Brown varnished neck and heads. Ten rosewood pegs. Six guitar strings and four extra strings. Original bridge. Length: 112.5cm, scale: 68.3cm" Photos courtesy Jean Michel RENARD - Old Musical Instruments |

The Scherzer 10 String Guitar 1862 |

The Romantic 10-string guitar in step-wise tuning is strung with frets on the first 6 strings as normal, with additional floating bass strings. Romantic tuning, we can assume from written period music, was tuned 10=A 9=B 8=C 7=D, followed by the normal 6 strings. This tuning is sometimes referred to as "Romantic" tuning today, or as "Baroque" tuning (presumably because the tuning may be useful for transcriptions of Baroque music). In addition to 19th century guitar music, the 10-string guitar is useful for Baroque music of Weiss, Bach, Baron and others which utilize an extended bass note range in counterpoint, and for 8-course and 10-course Renaissance lute music. The amount of material available to transcribe on the internet is vast; I use the Django software and library primarily. According to Gary Southwell: "Johan George Scherzer - Scherzer was apprentice to the famous Stauffer along with another noted maker C.F. Martin. While Martin moved to America, Scherzer stayed in Vienna and eventually took over his master’s business. He is known to have won first prize for 'best guitar' at the celebrated guitar competition in Brussels 1852 organized by Makaroff. Revered especially in Russia during the late 19th century Scherzer has remained relatively unknown to modern guitar enthusiasts. Although there are few surviving instruments, his reputation is due for re-examination. Having had the pleasure of studying many of the known examples of his work I feel he should be regarded amongst the very finest guitar makers of all time. The celebrated guitarist, Mertz, is known to have used Scherzer guitars." |

Mail@EarlyRomanticGuitar.com

Mail@EarlyRomanticGuitar.com